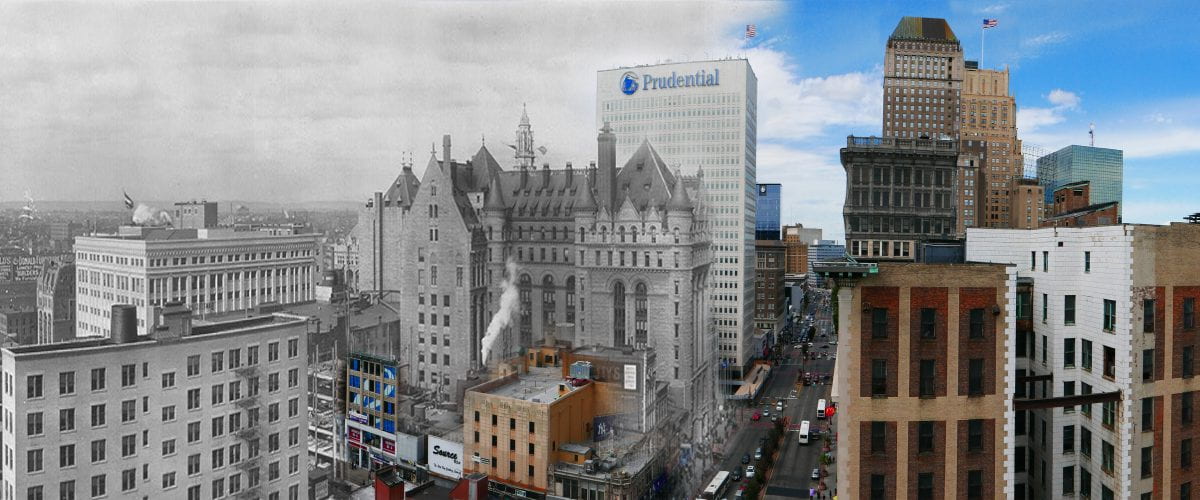

This animation visualizes 272,000 data points spanning 220+ years of the U.S. census since 1790. With data from the National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) at the University of Minnesota, I geo-referenced racial dot maps for all ten year intervals since 1790. Overlaying and fading time-lapse cartographies into each other reveals the scale of environmental and urban change.

● Each dot represents 10,000 people.

Top ten largest cities for each decade are labeled in orange.

Musical accompaniment by Philip Glass from the 1982 experimental film Koyaanisqatsi. In the Hopi language of the indigenous peoples of Arizona, the word koyaanisqatsi means “life out of balance.”

As you watch the map, ask:

1. How is the transformation of Indigenous lands into ranches and farmlands made visible in this film?

2. How do immigration and state policies change the built environment? In what ways are immigration and the law visible from the bird’s eye view of this film?

3. How has slavery influenced the demographic landscape and sequential racial dot maps shown in this film?

4. How do changes in transportation technology – in the sequential eras of the canal, the railroad, the highway, the airport, and now the internet – impact how people settle and distribute themselves across the built environment?

.

Sources:

1. Steven Manson, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, Tracy Kugler, and Steven Ruggles. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 17.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 2022. http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V17.0

2. Social Explorer. https://www.socialexplorer.com/