.

“Through Penn Station one entered the city like a god. Perhaps it was really too much. One scuttles in now like a rat.”

– Vincent Scully

.

.

View of Penn Station from roof of Macy’s department store c.1910

.

“Human beings, myself included, have an unfortunate tendency to appreciate people and things only after they are gone. Pennsylvania Station is the catalyst for the historic preservation movement.”

– Kenneth Jackson

.

.

The accompanying audio is accurate to what the place sounds like from the locations shown. The audio for old Penn Station is my imaginative reconstruction of how the original station might have sounded like, based on recordings from MoMA. My project was also inspired by this 2015 New York Times article about the subtle influence of sound on how we experience urban space: “Penn Station’s low ceilings suppress sound, which becomes hard to make out, an audible metaphor for its rat’s maze of architecture.”

“You feel that your life is being lost in a room where sound dies. We need reverberation.”

– architect Renzo Piano on the design of the current Penn Station

.

.

Main façade in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

Main façade in 2019

.

When New York Penn Station opened in 1910, the Pennsylvania Railroad boasted in advertisements that their vast new station was built of travertine marble from the same ancient Italian quarries as the Coliseum and Pantheon. Old Penn Station was rich in the architectural language of Greece and Rome. The façade comprised a colonnade of massive, Doric columns that stretched almost 450-feet end-to-end; it was inspired from temples on the Greek Acropolis. The main waiting room, at 314-feet-long, 109-feet-wide, and 150-feet-high, was modeled on Rome’s Baths of Diocletian. The project was as much an aesthetic gesture to the emerging City Beautiful Movement as it was a political statement: The Pennsylvania Railroad was here to stay, as permanent as the Penn Station it built.

The finished station, however, was an architectural contradiction. The Neoclassical exterior concealed what was, belowground, an extensive and, at-the-time, hyper-modern system of tunnels, electric trains, and communication systems that conveyed millions of people, baggage, and mail from street-level to each of 21 platforms. Aside from the solid stone columns of the main façade, most of the interior was of thin limestone, marble, and plaster sheets mounted on a metal structural frame. The seeming permanence of the stone walls was a cover for the steel frame and modern technology within on which this Neoclassical stage-set rested.

.

Metal frame during construction, before application of stone cladding

“Stone” column in the waiting room reveals structural frame during demolition.

.

Just over fifty years later, on October 28, 1963, demolition began. The Pennsylvania Railroad, burdened with debt and aging infrastructure, was selling off its most profitable real estate assets – its land, buildings, and equipment – to stay afloat until it declared bankruptcy by 1970. Through the same two Hudson River tunnels that building materials for the original Penn Station were delivered, some of the same rubble now passed. Much of this rubble was carted off and dumped in the New Jersey Meadowlands adjacent the tracks where commuter trains still pass. The Pennsylvania Railroad used, quite literally, the station’s technology to cannibalize itself, and as the foundations for the new, and current, Penn Station.

Searching for remnants of old Penn Station, I found historic photos from the New York Public Library, Historic American Buildings Survey, and Library of Congress. I returned to the same locations in fall 2019 to re-photograph these images from the identical camera angles. The resulting and visible ghost of the lost Penn Station presents a strong-clear vision of what Penn Station used to be, and by extension, what it could return to, given financial commitment and political will.

.

Concourse near track 16 in 1935-38 by Berenice Abbott

Concourse near track 16 in 2019

Train concourse: past and present from the same location

.

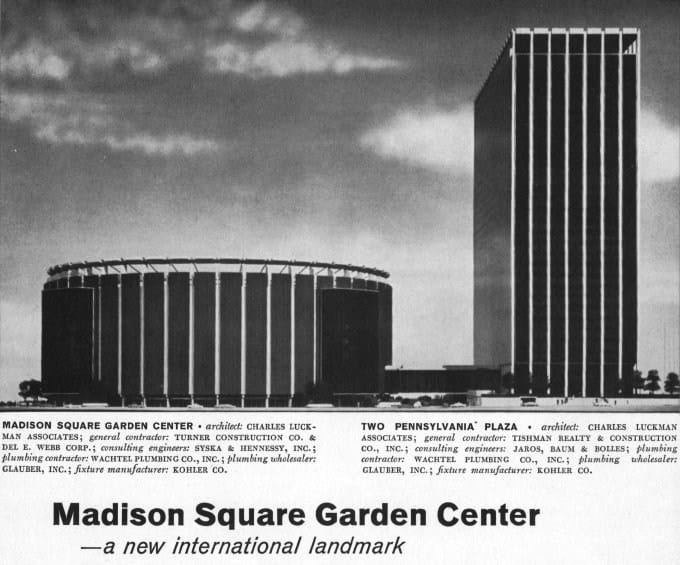

The current subterranean warrens represent a clean break from what was here before. As long as Madison Square Garden chokes Penn Station for air and light from above, the current lightless and oppressive Penn Station is here to stay. The current station’s cheap ceilings of corrugated metal, garish electric signage, and exposed concrete floors ironically proved more durable than the Roman marble and limestone of old. The current station is not so fleeting and has, in fact, existed longer on this site than the station before it.

Surprising still is how, for many New Yorkers, it seems inconceivable that the permanent and imposing appearance of the original station could, one day, vanish without a trace. This old station is more dream than reality, and it seems almost impossible to imagine the current arrangement as having anything to do with what came before. So little of the original station – and the pride in civic life and New York City this station stood for – remains visible. Interestingly, more of the original architectural fabric survives belowground than meets the eye aboveground.

.

Main façade in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

Main façade in 2019

View from corner of 31st Street and 7th Avenue in 1962 and 2019. The structure is unrecognizable aboveground.

.

.

32nd Street entrance c.1911

32nd Street entrance in 2019

.

1963 by Walker Evans

2019

.

South façade in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

Now Madison Square Garden in 2019

32nd Street entrance to waiting room in 1962 and 2019

The southeast corner of the still-standing General Post Office is in both frames, in the far left hand distance.

.

.

Plan of Old Penn Station

Plan of current station

.

In the five years that demolition and rebuilding lasted (from 1963 to 1968), Penn Station remained in active service. While builders demolished the old station above, commuters continued to pass by on the platforms and corridors below. For this brief moment, the two buildings lived side-by-side, until the present building swallowed almost all visible traces of the past. In spite of this loss, the confusing floor plan of the current Penn Station has much to do with remaining traces of the original. Column for column and void for void, the current Penn Station is built within the fabric of the original. The old Penn Station, completed 1910, had 21 tracks on 11 platforms. The new Penn Station has 21 tracks on 11 platforms. In the demolition process, not one track or platform moved. In the five-year re-construction process, none of the tracks and platforms were moved, and most of the stairs between concourse and track-level survived. This similarity enables us to situate parts of the old structure in relation to the new.

.

Frame of new Penn Station rises simultaneous to the demolition of the old c.1963-68.

Passengers in train concourse as new structural frame divides them from the soon-to-be-demolished glass canopy of the old station.

Frame of new Penn Station rises simultaneous to the demolition of the old c.1963-68

Passengers in train concourse as new structural frame divides them from the soon-to-be-demolished glass canopy of the old station.

.

Concourse near track 6

Concourse near track 6

Train concourse before and after insertion of the new structural frame, from the same camera angle

.

.

.

.

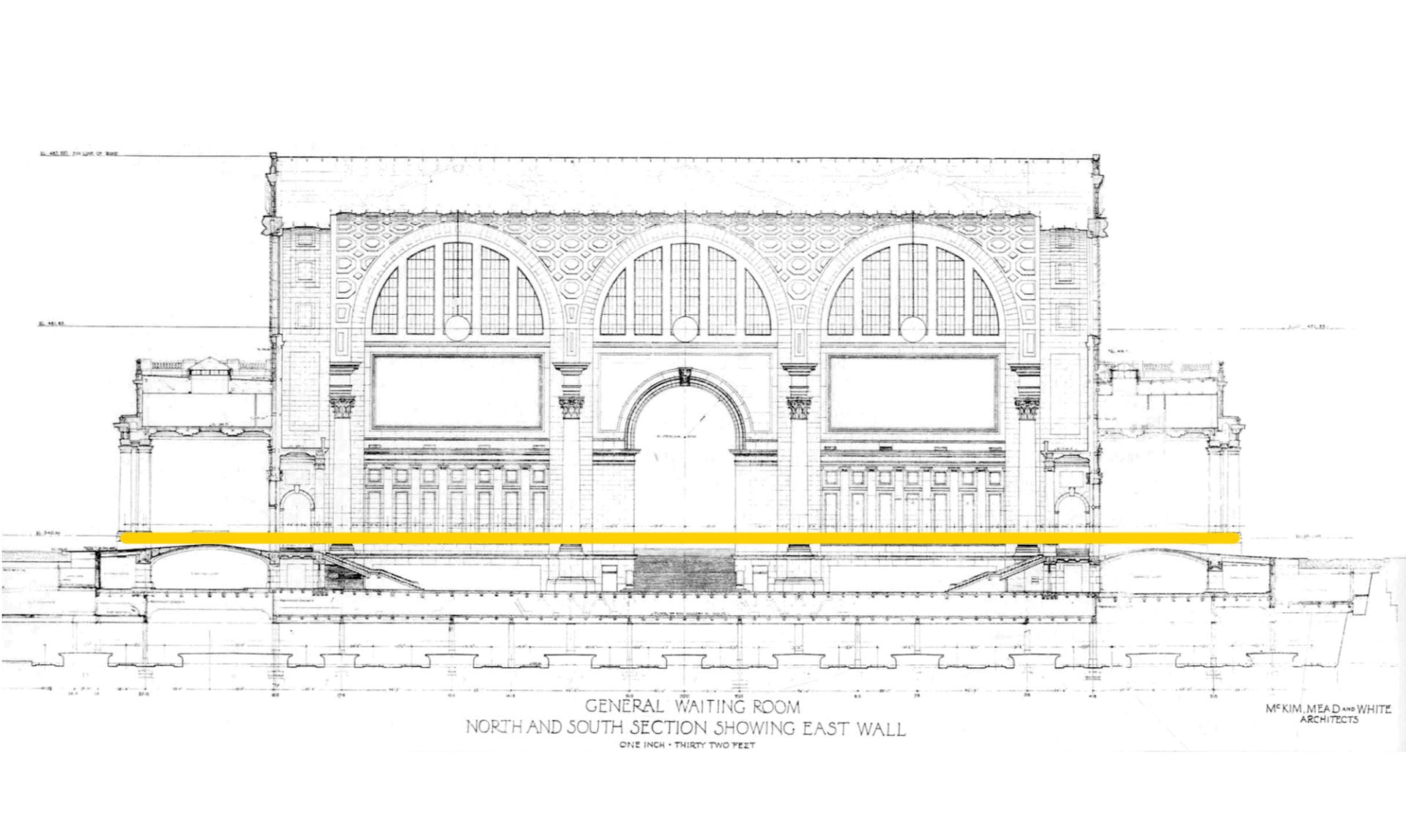

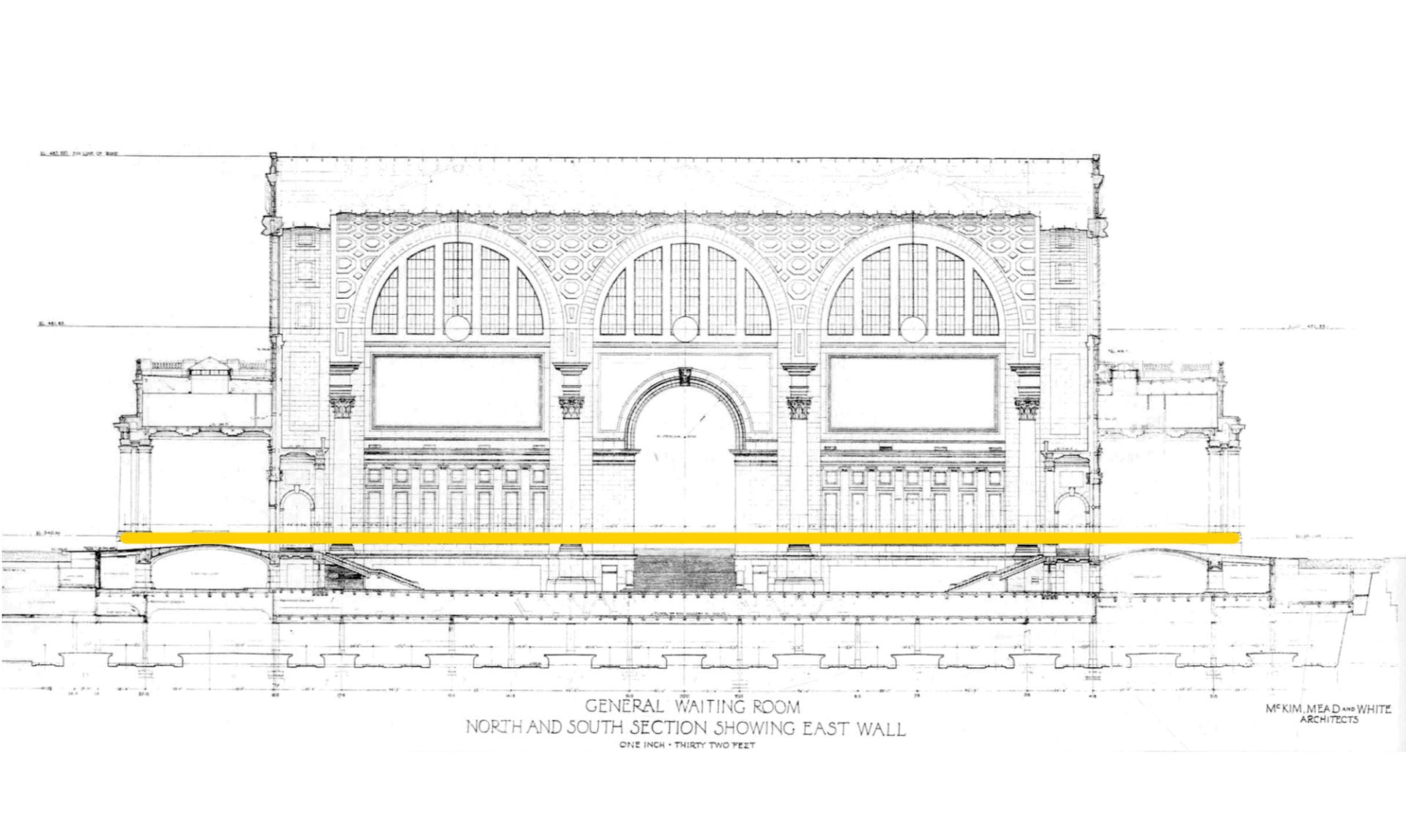

The above cross-section of old Penn Station’s waiting room shows the extent of change. The orange line indicates the elevation at ground-level to which the architectural fabric of the old building was demolished. Above this line, nothing of Penn Station survives. Below this line, most of the original structure, tracks, infrastructure, stairwells, and the general contours of the original rooms survive, except now hidden.

After the Roman Empire collapsed, its architectural monuments to empire and power fell into disuse; many were repurposed for more humble and practical purposes. The Coliseum became a stone quarry, the Roman Senate House a humble church, and the Theatre of Marcellus a medieval fortress. New purposes were developed in the shells of old monuments. When a building is reused and altered but still bears visible traces of its earlier form, architectural historians call this creation a palimpsest. A palimpsest is neither of the present nor of the past; it is a mixture of both. For instance, the two square fountains of the 9/11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan mirror the locations of the now-vanished Twin Towers. For a modern and young city in world terms, Penn Station is New York City’s largest palimpsest.

.

Arcade at entrance to waiting hall in 1905-15

Now a basement in 2019

Shopping arcade in 1911 and 2019

.

.

Waiting hall

Now a basement in 2019

View from 7th Avenue shopping arcade into the waiting room in 1911 and 2019

.

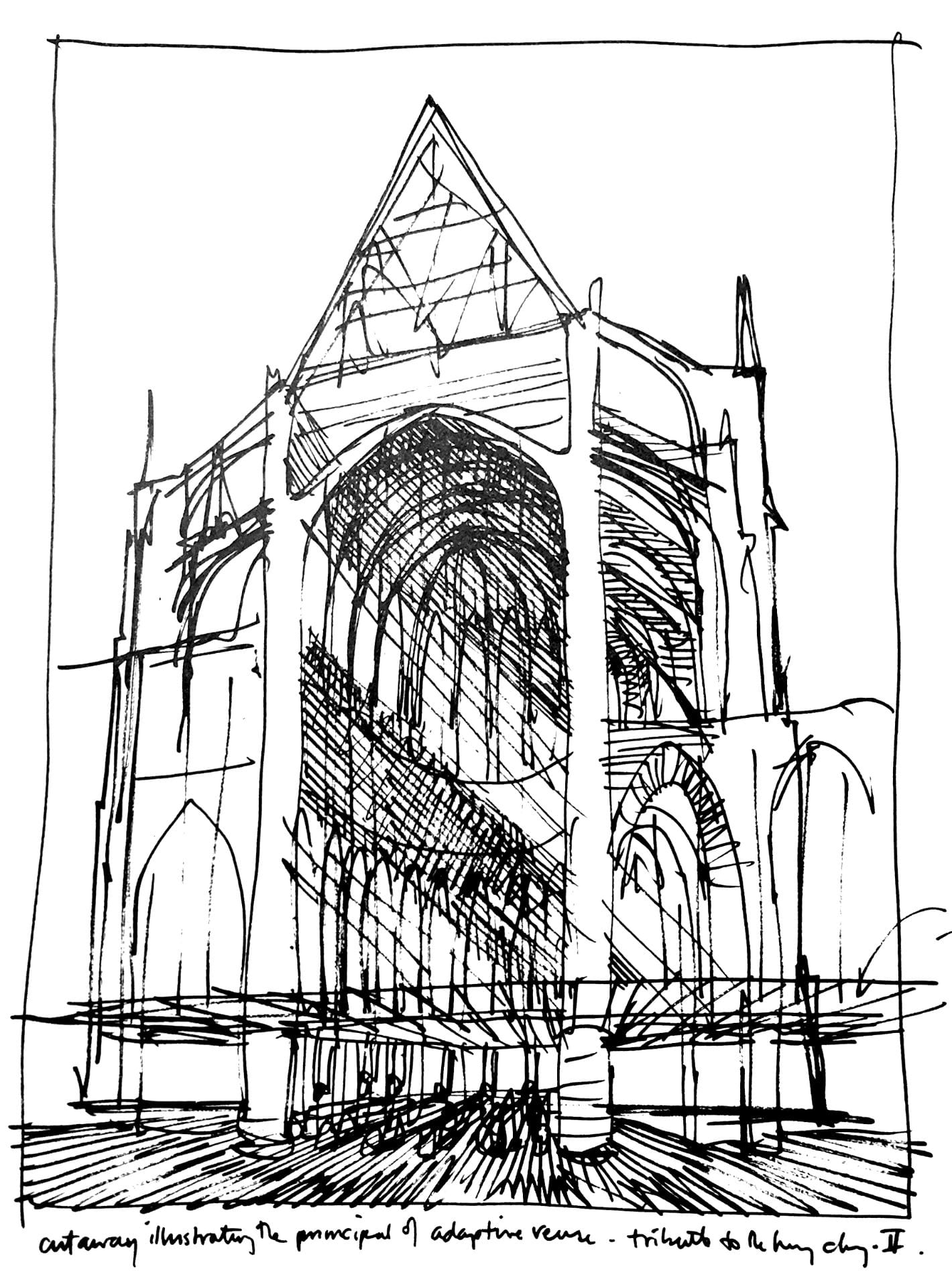

“Cutaway illustrating the principle of adaptive reuse.” Drawing by architectural children’s book illustrator, David Macaulay, proposes to discard the “non- functional” spaces of the medieval cathedral by erecting a Styrofoam drop ceiling just above the floor. Everything above – light, soundscape, and ornament is “superfluous” to the cathedral’s function.

The oppressively low ceilings of the current station are the structural division between the public areas belowground and the now private (formerly public) areas aboveground. These ceilings also align to the border between the infrastructure of the original station that survives and the architectural fabric that was lost.

The Pennsylvania Railroad made the decision that made the most economic sense: to keep the infrastructure beneath and decapitate the “non-functional” aesthetics of the soaring ceilings and open spaces aboveground. This was valuable land that could be put to more profitable use. Into these empty “air rights,” the corporation could insert Penn Station’s new functions of Madison Square Garden and office towers that would, at last, generate additional income. While exploring the station, I discovered this palimpsest valued the practical and made absolute economic sense: Who needs to enter the city on the scale of a titanic-sized god when humans require spaces no higher than 8-feet-high to pass through?

.

Concourse from south entrance in 1910

Concourse from south entrance in 2019

A cathedral with a drop ceiling

.

.

Arcade in 1911

The same space in 2019

The shopping arcade in 1911 and 2019

Statue of Samuel Rea is in the shadows.

.

President Samuel Rea

The nuances of this palimpsest become clearer from inside the building. Passengers entering the old station proceeded down a long shopping arcade to the waiting room and platforms. What was once public space is now the private lobby of the commercial offices aboveground. On the right hand side, in the shadows of the private lobby, stands a statue of Samuel Rea, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. A century ago, Rea stood at the entrance and welcomed passengers and the public; he now stands and watches the corporate clients and office workers. In old Penn Station, an inscription beneath announced his name and title. In the current location, Rea is out of place and has no relationship with his surroundings; the once prominent inscription is almost invisible on the new tablet behind him.

.

Waiting hall toward arcade exit in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

The same space in 2019

Statue of Samuel Rea is in the left hand niche.

Almost stone for stone, the location of the current waiting room escalator mirrors the location of the original.

.

.

Waiting hall in 1911

The same space in 2019

Main entrance to waiting room: The left hand niche contains the statue of Alexander Cassatt, Pennsylvania Railroad president during construction.

.

.

Waiting hall in 1911

Now a parking lot

The waiting room, once the largest indoor public space in New York City, is now a parking lot.

.

From the street-level arcade, passengers descended into the cavernous waiting room, sunken a few feet belowground. While the room itself is gone, the contours of this room survive in the general footprint of the sunken parking lot that now occupies the site. What was once public space is now private and patrolled by Madison Square Garden security guards who forbade me from standing at this location with my camera.

.

Waiting hall in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

The same space in 2019

Perhaps, beneath this asphalt parking lot, fragments of the original waiting room floor remain.

.

.

Concourse in 1935-38 by Berenice Abbott

The same view in 2019

Train Concourse

.

.

Concourse c.1930

Concourse in 2019

Train concourse, past and present.

White cutouts on the drop ceiling mirror the former locations of the demolished skylights.

.

.

Concourse c.1905-1915

Concourse in 2019

.

Concourse northern exit near track 16

Concourse northern exit near track 16 in 2019

.

Concourse near track 10 in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

Concourse near track 10 in 2019

.

Concourse from track 6 c.1910-15

Concourse from track 6 in 2019

.

Concourse in 1962 by Cervin Robinson

The same view in 2019

This part of the train concourse is now the VIP entrance for spectators at Madison Square Garden.

.

The design problems with the current Penn Station are similar to those of old Penn Station: too few tracks, too many passengers, confusing circulation, and outdated infrastructure. After all, it is not the engineering and infrastructure that set these two buildings apart, as brick-for-brick and beam-for-beam, the 1960s rebuilding did not generally alter the areas belowground. This early-twentieth-century infrastructure was, after all, designed to handle no more than 200,000 passengers-per-day, and yet now struggles under the burden of 650,000-per-day. Instead, it is the envelope around this infrastructure that was rebuilt in the 1960s, and whose loss the public and historians now mourn.

.

Track 6 c.1910-15

Track 6 in 2019

.

At track-level, the railroad ties, location of the third rail, and support columns are original to 1910. The columns in the foreground were added in the 1960s to support the weight of Madison Square Garden. The columns in the distance are original to 1910. The 1960s modernist buildings above conceal below what is, in essence, early-twentieth-century infrastructure.

.

Track 6 c.1910-15

Track 6 in 2019

View from Track Six

.

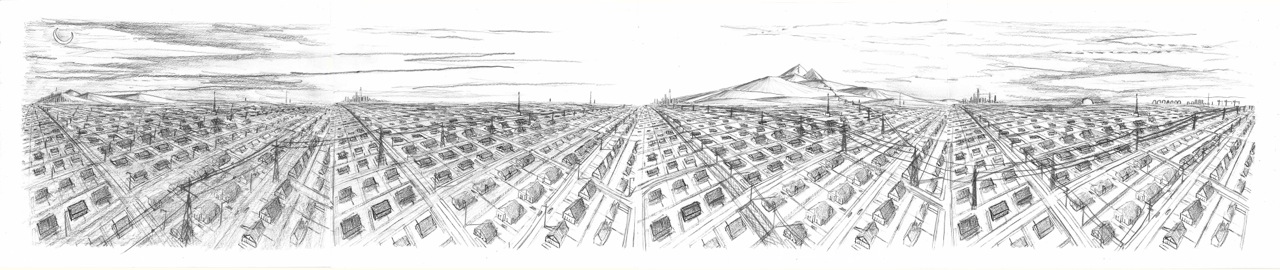

Generations of New Yorkers hoped Penn Station would one day be restored with an architectural monument befitting New York City and the Western hemisphere’s busiest train station. In addition to rebuilding the General Post Office next door, other proposals over the years have called for rebuilding Penn Station exactly as it appeared before, or imagining a futuristic Penn Station emerging from the structural shell of the current Madison Square Garden, entitled “Penn Station Palimpsest.” Precedent exists for both proposals. Some post World War II cities rebuilt their monuments and bombed out city centers as they appeared before (such as Dresden and Warsaw), while others incorporated the rubble of the lost buildings into a modern building (such as Coventry Cathedral in England and Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin). What we miss about old Penn Station was not the infrastructure, operations, or even the building itself, but rather the way this architecture made us feel dignified, and which we feel no longer.

.

.