Speech given in July 2025, at the Newark City Council’s monthly Hearing of the Citizens:

.

Link to full length recording of meeting (five hours)

Attached sources:

+ Covanta’s damage to Newark, a fact sheet

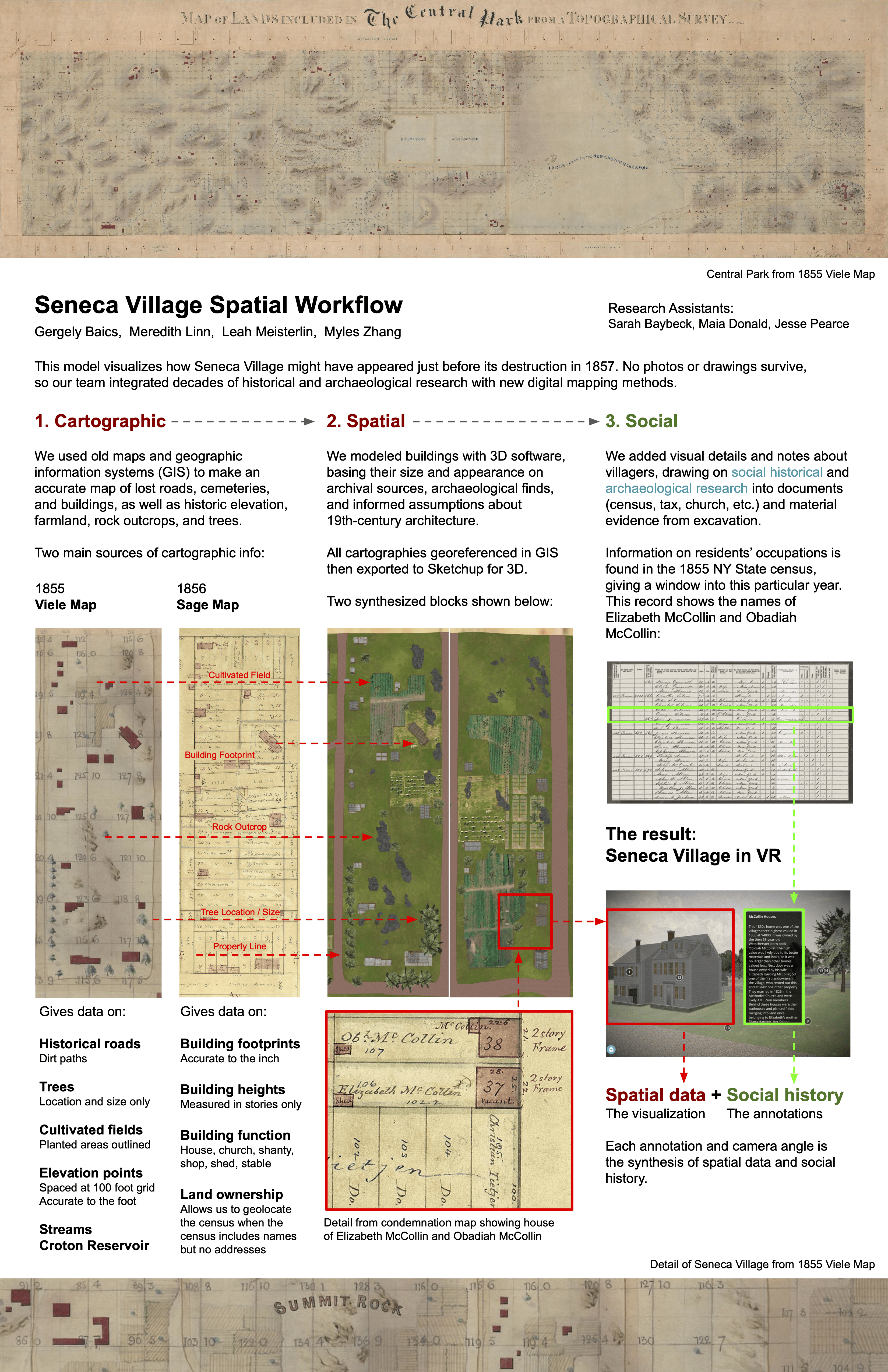

Written 2025 by Myles Zhang

+ Contract between Covanta and New York City

Signed 2012, result of OPRA request submitted to New York City Department of Sanitation

+ Transcription of Spoken Remarks:

Hello Council,

My name is Myles Zhang, and I’m a lifelong Newark resident.

I’d like to speak today about the trash incinerator in Newark, specifically the Covanta incinerator. As you know, a very large percentage of Newark’s land area is owned by the Port Authority and Newark Airport. And they pay Newark a licensing fee. But they can choose to use that land how they want to. One of those land uses is for the Covanta incinerator.

The Covanta incinerator burns at least 985,000 tons of trash a year, and it burns about 2,700 tons of trash a day. They’ve had contracts with about twenty municipalities. One of those contracts happens to be New York City. New York City pays about a $700 million contract over 20 years for the Covanta facility. When you look at that contract, that contract requires that New York City provide the Covanta facility with 352 trucks per day of garbage. So we’re burning several thousand tons per day from 352 trucks per day.

Not only is New York City required to provide the Covanta facility with that number of trucks. But if they fail to provide 352 trucks per day, New York City has to pay a penalty to Covanta for not giving them enough trash to burn. And that penalty is equal to 85% of the cost of burning the trash. So if New York City provides a ton of trash and pays a $100. And then one day they didn’t provide that ton of trash, they’d pay $85 in fees. Basically, Covanta has a very lucrative contract, a contract that has a guaranteed revenue. Regardless of if the municipality provides them that trash or not, they still get paid. Furthermore, there is a perverse incentive to burn trash at that facility because if they don’t burn enough trash, there’s a high penalty here. The consequences for Newark are more than obvious, right.

The trash burned in Newark is produced specifically from the New York City census tracts representing the Upper East Side and Upper West Side. The median income in the Upper East Side and Upper West Side is over $150,000 a year. And that trash is being burned in Newark, where in the Ironbound the median income is under $50,000 a year. So in other words, the trash from the wealthiest community in the United States is being burned in one of the poorest communities in the United States.

So what does the City of Newark get for all of this? Well, for one thing, the port and the airport are the two most valuable pieces of real estate in Newark. About $500 billion a year in commerce passes through the port and the airport. And $700 million of trash is being processed in the Covanta facility. But the majority of Newark taxpayer revenue is not being paid by the port and the airport, even though the port, airport, and the Port Authority’s contract with Covanta are among the most valuable pieces of real estate in Newark.

For instance, if you look back, one contract that the City of Newark made in 2021 was the Host Municipality Fee for the Covanta facility, which was about $2-3 million a year. But if we break down the cost of the contract by the amount of trash burned, for every $100 that New York City pays Covanta to burn its trash, the Host Municipality Fee as a percentage of that cost of burning trash is about 70 cents. So 0.7% of the money that New York City pays to Covanta gets cycled back to the City of Newark. That is 0.7% of $700 million.

Newark is being ripped off. Newark is getting the short end of the stick. And this is a systemic pattern here. I think one thing that this council should distinguish is between winning the battles vs. winning the war, right. We can get a higher deal, a better deal from Covanta. We can get a better trash incinerator. We can get another Amazon warehouse, which you call winning the battle. But what does winning the war look like?

For me, winning that war means you don’t have that trash incinerator here. You don’t have that Amazon warehouse here. You don’t have those polluting industries here. You have better industries for a larger vision of the city. So I encourage this council to aggressively pursue action against the Port Authority, against Covanta, so that Newark gets paid its fair share of the $500 billion in retail volume that passes through Port Newark.

Thank you. And keep up the fight.

Developed with input from James White,

Developed with input from James White,