Newark’s parking and land use crisis

.

Edison ParkFast, among several Newark institutions such as Rutgers and the New Jersey Institute of Technology, engaged in the systematic destruction of our city’s heritage. In the James Street Commons Historic District, for instance, Edison ParkFast and Rutgers are the single largest contributors to demolition of historic properties from 1978 to the present. Both demolished dozens of historic Newark homes and factories. As Edison ParkFast continues to consolidate its properties into ever larger parcels, the question arises: How will this entity develop this land? Will future development respect old Newark and our history?

Too often, the name of progress is invoked to justify the destruction of old. New development, from Newark’s $200 million sports arena to Panasonic’s $200 million new headquarters, reveal that our new architecture is often out of time, place, and scale. Not often enough do Newark leaders realize that progress is enriched by using the past as the foundation for redevelopment efforts. One can walk through Brooklyn or preserved parts of Manhattan and compare those historic streetscapes to Newark. Newark once had the types and varieties of architecture that Brooklyn still does, but Newark followed the short-sighted path of demolition and urban renewal.

Click here for interactive map of Newark past and present.

Here is a speech I gave before the Newark City Council on 19 May 2016 in protest to Edison’s anti-urban practices:

.

Good evening ladies and gentlemen of the Newark City Council.

My name is Myles. I am a proud, lifelong Newarker.

Newark is a city surrounded by asphalt.

To the south lies our port and airport, comprising 1/3 of Newark’s land area. Our airport handles 40 million passengers a year. Our port handles over a million containers of cargo a year. Both pollute our air.

Our city is surrounded by highways: Route 78 to the South, The Parkway to the West, Route 280 to the North, and McCarter Highway to the East. Millions of car travel these congested highways every year.

Our urban core is buried in asphalt. Thousands of commuters per day. Millions of cars per year.

Edison Parking is beneficiary of this pollution. Their 60 thousand parking spots are valued in the billions. They make millions on the land of buildings they demolished often illegally. They pay no water bills; their water runs off their lots and into our sewer mains. For a company so wealthy; they contribute little to the health of our city.

One in four Newark children have asthma, far above the national average. Chances are that your children or the friends of your children also have asthma.

I, too, have asthma. Always had. Always will.

Enough is enough. It is time to develop our city sustainably. Public transportation. Public bike lanes. Public parks. Sustainable infrastructure.

Edison Parking is not a sustainable corporation. When our zoning board approves of the illegal demolition of our historic architecture, they are complacent in this violation of our law. When our zoning board sits silently as Edison Parking uses our lands for non-permissible zoning use, they are not upholding the laws they are subject to.

It is time to change. You, as our elected officials, are in a position to enact the change your public needs. You, as informed citizens of Newark, are responsible for holding corporations accountable to our laws.

This is not a question of complex ethics or morality. It is a matter of common sense. Edison Parking has and continues to demolish our heritage, pollute our air, and violate our laws. Edison parking is breaking its responsibility to the public. Will you hold them accountable?

Please consider the city you want for our children and our future.

Thank you.

.

Comparative views of my neighborhood, past and present

These views compare my neighborhood in the 1960s and today, hinting at the kind of human scale urban fabric demolished.

.

Central Avenue between Broad & Halsey in 11959, demolished by Edison Parking

Central Avenue between Broad & Halsey in 1978, demolished by Edison Parking

Corner of Central & Washington in 1959, demolished by Edison Parking

Washington Street between Bleecker & Central Avenue in 1978, demolished by Edison Parking

Mulberry & Market in the 1950s, currently owned by Edison Parking

86-88 University Street, demolished by Rutgers

Washington Street School for the Dead in 1978, demolished by Rutgers

Eagle Street in 1978, demolished by Rutgers

15 Burnett Street in 1978

University Street in 1978, demolished by Saint Michael’s Hospital for emergency parking

Park & Clinton Avenues in the early 1900s, currently a parking lot for Sacred Heart Cathedral

Temple B’Nai Abraham, demolished to construct parking for the Essex County Hall of Records

The 18000-seat Tivoli Theater in Roseville section of Newark, demolished to constuct low-income housing project

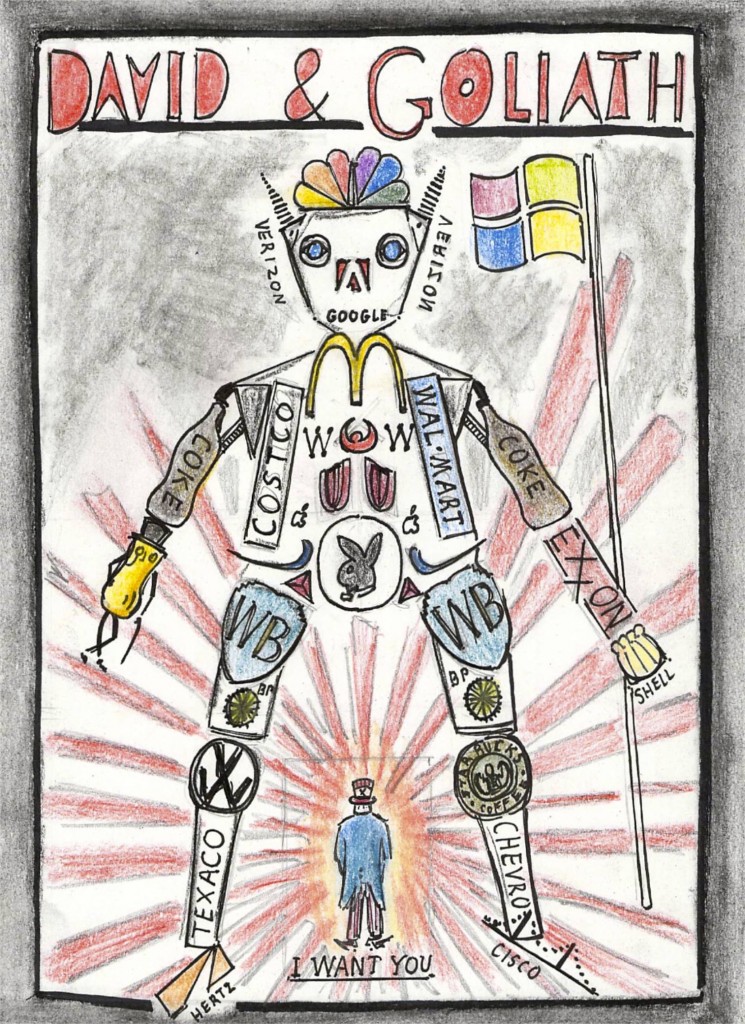

A Goliath made of corporate logos fights a tiny David dressed as Uncle Sam.

A Goliath made of corporate logos fights a tiny David dressed as Uncle Sam.